In London's British Library, among the treasures like the Magna Carta and the Lindisfarne Gospels, there is a remarkable collection of simple personal items. These objects, including two steel bracelets, a small dagger, a needle and thread, a conch shell, and a seal ring, belonged to Bhai Maharaj Singh (d.1856), a spiritual leader and passionate Sikh nationalist. They hold an extraordinary story from the final days of Sikh sovereignty in Punjab. These seemingly ordinary belongings were taken from him when he was arrested in the year after the Anglo-Sikh wars in 1849. Today, they are carefully preserved in the library.

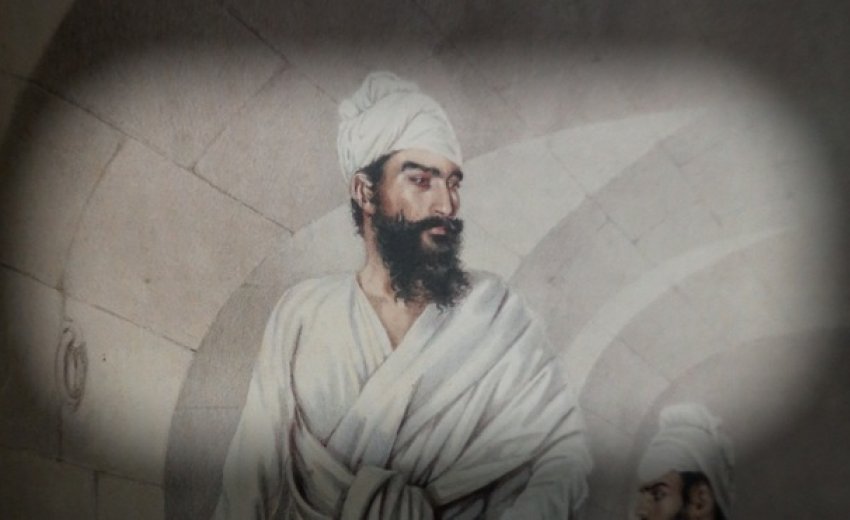

Bhai Maharaj Singh

Bhai Maharaj Singh served as a source of inspiration for many ordinary Punjabis and posed a significant challenge to early colonial ambitions in the region. His influential role and revolutionary actions against the British during the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-49) were acknowledged by The Times of London. The newspaper noted that he held immense sway among Sikh chieftains and the entire population of Punjab. It was widely believed that he played a central role in various conspiracies and uprisings that resulted in significant loss of life and expenses in Punjab.

Following the surrender of the Khalsa Army to British forces in 1849, Bhai Maharaj Singh was arrested and swiftly sent into exile in Singapore. He spent six years in solitary confinement there before passing away in 1856. Even today, he remains a significant figure for the Sikh community both in Singapore and Punjab.

His personal belongings stored at the British Library were taken away from him when he was arrested. These possessions offer a remarkable understanding of this remarkable Sikh leader. The pair of simple steel bracelets (kara) and the small dagger (dastar vali kirpan) are highly personal and intimate items. A humble sewing needle and thread, seemingly ordinary yet essential for a travelling warrior. The conch shell represents his role as a spiritual leader. The only evident symbol of grandeur is the seal ring, engraved with the phrase "Akal sahai Maharaj Singh ji" in reverse Gurmukhi script, which translates to "The Immortal One protects: Maharaj Singh ji."

The objects and manuscripts have been part of the British Museum's collection since the 1920s. They were gifted to the institution by a direct descendant of the man who ultimately apprehended the Bhai in Jalandhar. Ever since their arrival, these items have been kept in secure storage, along with the rest of the India Office Collections. The bracelets, kirpan, and ring remain in pristine condition. Even today, the needle and thread can still be used, and the conch can produce its distinctive sound if blown into.

However, these artefacts are not the only ones associated with the Sikh holy man in the British Library's vaults. The collection also includes four of his personal manuscripts, all written in the Gurumukhi script. These manuscripts have been meticulously catalogued as part of a national project undertaken by the United Kingdom Punjab Heritage Association (UKPHA) to document Punjabi manuscripts in UK national collections. Harminder Singh Mann, the senior cataloguer at UKPHA, highlighted their significance, stating that each manuscript, ranging from a single page to a short anthology, provides valuable insights into the life of one of the most intriguing figures in Sikh history. Mann further informed Punjab Heritage News that the British Library's meticulous preservation of these precious manuscripts ensures that they can be enjoyed and studied by future generations.

Early life

Bhai Maharaj Singh, originally named Nihal Singh, was born in Rabbon, Ludhiana. During his early life, he was influenced by Bhai Bir Singh of Naurangabad and took over his position after his death in 1844. At that time, he had already become a prominent religious leader in the Sikh courts of Lahore. As British influence and interference in the court increased, Bhai Maharaj Singh remained uncompromising in his message, which was highly nationalistic. In 1847, his transformation into a saintly revolutionary was solidified when he was implicated in a conspiracy to assassinate Henry Lawrence, the British resident at Lahore. With his property seized and being wanted by the British, he went into hiding with 600 followers to continue his subversive activities. The governor-general of that time, Lord Dalhousie, offered a staggering reward of Rs. 10,000 for his capture.

British captured him

Bhai Ji was finally captivated by the British towards the end of 1849. Henry Vansittart, along with twenty cavalry irregulars, engaged in an armed confrontation and successfully captured Maharaj Singh in the Jalandhar district. Vansittart expressed the British perspective on Bhai Ji's influence and their deep frustration with his continuous subversive activities through the following statement: "The Guru is not an ordinary man. To the natives, he holds the same significance as Jesus does to the most devout Christians. Tens of thousands witnessed his miracles, which are believed more implicitly than those performed by the ancient prophets." The Times of London also provided additional evidence of Maharaj Singh's influence in a report: "He is revered by all factions and social classes due to his alleged ability to perform miracles. In fact, he is considered the only holy man and prophet of the Punjab."

Soon after his arrest, the Punjab descended into chaos. There were concerns about a plot to rescue him from prison, and six Akali Nihang followers launched a suicidal attack on a British army cantonment in Lahore.

The fear of sparking a mutiny or guerrilla war prevented a swift execution. The British authorities quickly made plans to exile him to the infamous Outram Road Jail in colonial Singapore. Bhai Maharaj Singh spent his final six years in the filthy confines of Outram Road. He passed away in 1856, and a stone slab marked the location of his cremation.

Even after his death, his legend continued to thrive. The local Tamil and Chinese communities in Singapore visited his cremation site to worship his funerary stone. In 1966, the stone was relocated to the Silat Road Gurdwara on the island.

*Based on an article by Amandeep Madra and Parmjit Singh on 1st July 2008