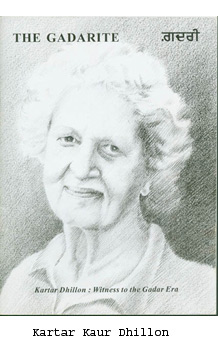

Jasbir Singh Kang recently sent us a rare interview with Mrs. Kartar Kaur Dhillon who passed away at age of 93 on June 15th, 2008 in the Bay Area. She was born in California in 1915, and witnessed many important historical events which affected our community and world at large.

Jasbir Singh Kang recently sent us a rare interview with Mrs. Kartar Kaur Dhillon who passed away at age of 93 on June 15th, 2008 in the Bay Area. She was born in California in 1915, and witnessed many important historical events which affected our community and world at large.

After watching the docudrama Turbans in year 2000 I invited its director Prof Erika Surat Andersen from UC Los Angles to Punjabi American Festival in Yuba City. But Prof Andersen advised me rather to invite her grandmother to our event since her movie was based on the Kartar Kaur Dhillon's Memoirs from 1923. Even though some considered it controversial movie but it brought tears to many eyes. I was astonished to meet this elderly fragile lady in her eighties with an unbelievable resolve to fight against injustice in this world. She made a touching speech at the festival and at least I was convinced to visit her home in Oakland, California on September 1st 2001 to record her video interview to learn about the history of her family and to find the source of her determination and passion. She passed away at age of 93 on June 15th, 2008. Below is a transcription from my video interview. We may or may not agree with everything she said but I hope we can all learn some thing from her.

1. When and why your family came to United States?

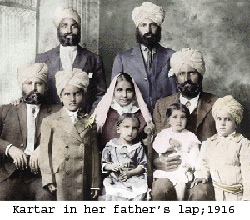

Answer: My father came to United States around 1890's and settled here in 1899. Previously he had come to San Francisco a number of times because he was working as a seaman at that point in his life and so he came to San Francisco and other ports in North and South America, but in 1899 that he settled here. He went back to India in 1910 at the requirement of his father who had arranged a marriage for him. So he married my mother Rattan Kaur and then they had 8 children here over the years. The first was born in 1910 and the last child was born in 1926. I was born in 1915 and I was the forth child.

2. Do you have any memories of growing as a child in new country, obviously it wasn't a new country for you, but for your parents definitely things were not accepting in those days. So do you have any memories as a child growing in US?

Answer: Yes, I do. If you want to know that were we not accepted, we definitely were not accepted, except that my father was fortunately able to speak both English and Punjabi very fluently and so he made it easier for us. But my mother never learned the language too well, because he could communicate with the outside world. We were put in school as soon as we were old enough to go to school. That was in Astoria, Oregon where my father was working in a lumber mill. People who lived here were European immigrants as we all know we all are immigrants in United States except the Native Americans who are the natives of this country. But the European immigrants who had arrived here earlier than my family for instance, thought it belong to them. We were not really any threat to them at that point. But later on when there were more Indians coming to this country then we became a threat to the labor unions and they felt that we would be taking away their work. But my father cleared their way there too because he belonged to the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) as soon as he started working in the lumber mill. It was a very progressive union, they believed that a union should be more than just a bread and butter issue of not just earning a living but what does a person do with his life outside of his job and that was important and that's why they were very good. But they were threat to old established unions. They don't have the respect in history that is given to the American labor, the Federation of Labor, etc.

3. Like you mentioned your father, but what about you as being as a child? Were you treated differently?

3. Like you mentioned your father, but what about you as being as a child? Were you treated differently?

Answer: Yes, of course, we were treated differently in the beginning but as we started going to school and holding our own. I guess the most spectacular thing that happened was that my brothers wore turbans to the grade school; and other kids thought it was a great fun to use snowballs to knock their turbans off. It took a lot of painful thought between my mother and father to decide that, "Well, so we are here and we are going to educate our children so why let be an issue about the turbans, they can remove their turbans and cut their hair and be like other kids, and have one less battle to fight and they can start wearing turbans against if they prefer to." My father of course did not remove his turban or cut his hair. So we kept the Sikh tradition in the family very powerfully. If it wasn't for that the fact that my father and mother retained their beliefs, we wouldn't had this strength to fight back at the kids who taunted us. Pretty soon they accepted us because we knew we weren't less than them and we wouldn't allow them to demean us in any way.

4. Were there any laws especially to discriminate against people from Asia or India in particular?

Answer: You know I don't have the actual figures in front of me, so I can't quote the years. But definitely, there were laws as soon as there were some people coming from India. Well earlier it was the Japanese who were considered undesirable because there were more of them and they had a powerful nation of their own. But they had some help from their governments because they had a government. But when Indian people started coming here; oh of course there were Chinese who had come here too, there was discrimination against them. Well I say 'we' although I was a kid, but we appealed to the British government which had our home, to which we were beholden by or taken over our country by force, and they gave us no support at all. I am thinking in particular of the incidence of the Komagata Maru in Canada and that was as case there was no help. Then there was another country in the common wealth ruled by Britain but they just would not help the people and I would not go into that story, because it's a powerful story of its own. The laws that affected us I think the earliest one might have been in 1917 they just said Indians could not own any property and they could not become citizens. But there were even stronger laws later than this that declared that (I don't know which came first.) Indians definitely could not own property and they could not become citizens and we could not vote and if you can't vote in a supposedly democratic country then you have no power and no democracy. None of that changed until after the token freedom of India from the British rule in 1947.

5. Sikhs looked different because they wore turbans. So it must be harder for them in those days. Do you remember any particular incident regarding this which stands out?

Answer: Well, I wasn't aware of the fact that it was because of the Sikhs being singled out I think all the Indians were singled. But they were just simply blanket refusal against Asians which also included the Japanese and the Chinese. I don't know much about it. 6. How about the workers, were there any problem getting the jobs as they looked different? Was it different for Sikhs who looked different from everybody else or it was the same?

6. How about the workers, were there any problem getting the jobs as they looked different? Was it different for Sikhs who looked different from everybody else or it was the same?

Answer: No, it was not like anybody else. They looked upon Sikhs and Indians generally as freaks as we had come out of circus of something. There was a great cruelty against our people. There was killing in the state of Washington. I don't have facts on my fingertips but I remember that in that state of Washington there was a massacre of our people and that was one of the worst things and then there was something in Wheatland (California) where people were also murdered and there were a number of incidents in which very cruel things were done to our people. Outside of the fact well about getting work, they always got work because they were such good workers. If they were in California, then they were already in Punjab and they had been farmers. They knew what to do and they knew about how to take care of land and cultivate things. And if they were in Oregon, where the lumber industry was, and then they were such hard workers, but they were paid less and this was the discrimination. They got one rate of pay while the European immigrants who were workers got higher rate of pay. When Erica (my granddaughter) and I were doing research about the movie 'Turbans' then we went through a lot of papers from the news on that day. One of the items that we read was how some boys (maybe they were men or just boys) bombarded a little house or little shack where our people lived in. A number of people used to live together so that they would cook and eat together. They had taken rocks and just damaged the house, just smashed it. Then this man (now a man earlier he was a boy) tells the story that he doesn't know how those guys got out of that house, but they escaped somehow. They were all gone by the morning. He said, "Next morning we didn't see them again" with pride that we got rid of them. No sadness about the cruelty that we had inflicted on people who just were living their lives, then just some pride that we got rid of the undesirable people.

7. As people looked forward for freedom of India from British rule at that time. You know there was movement called Gaddar Party in California for the liberation of India. Do you have any memories of your family and friends who took part in this movement?

Answer: Every member of my family was a part of it. We lived for the Gaddar party. The Gaddar Party was started in Astoria, Oregon where we happen to be living few years later. I was born in California in Simi Valley. We went to Oregon when I was just few years old. The thing about Gaddar partywas they had their founding charter made at a meeting in Astoria, Oregon in 1913 and later then moved to San Francisco. The thing about the Gaddar party was it was absolutely Non- Sectarian. They didn't care who was a Sikh, who was a Muslim, who was a Hindu. There was one objective that we had in our mind and that was to get the British rule out of India, to get the imposters out and to get rid of criminals taking over our country. And we stayed with this objective. People joined in from all over the world to join the Gaddar Party. We had centers in Berlin, in Hong Kong, and we had gathering from all over the world. People sent us money. There were people who had college educations and were able to communicate easily in English, wrote articles and gave speeches. But the main people, the main Gaddar party were comprised of the farming people from Punjab who really were the life and blood of the Gaddar Party. They had regular collections. They went around to my every farm and every place where one of our people was living and three men would go together: a Sikh, a Hindu, and a Muslim, because to show that we are doing this for our Hindustan and not for anything extra separate. They collected money and that's what kept Gaddar Party going and that's how we got a building in San Francisco, set up printing press, and sent out the message of freedom that we would settle for nothing less than freedom all over the world.

8. I have a question entirely different from what we talked about earlier. How do you see a process of assimilation in melting pot for your generation people and how do you see it in today's context.

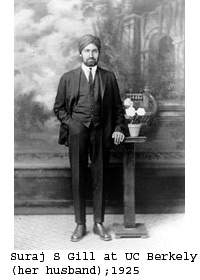

Answer: Well, you see this word 'melting pot'; I don't like it because somehow there's something disturbing about it. We are people and we are not put into a pot and melted down to it. We are people who come with very strong different cultures, with very strong different ideas. But here we have a chance to become truly international and that if there's any beauty in having become a part of this American civilization is that we have a chance to meet everyone from every part of the world. I am so pleased that in my family my one brother is married to a Mexican woman and other is married to an Irish woman. I think only the three sisters married the Indians, because I guess there were not that many people to choose from. My husband was a Gaddar Party activist. He was living at 5th Wood Street in San Francisco. He was a student at UC Berkley. But as soon he came to this country and started hearing the people talk about the Gaddar Party. He then became a Gaddar Party activist. He lived in the headquarters and helped print the Gaddar paper and gave lectures at the meetings. We had regular meetings every year like Gaddar Party had every year. The Sikhs had this in common with the Gaddar party meetings that there would be a Sikh Temple meeting in Stockton and we had only one temple at that time and that was in Stockton, and then there would be a Gaddar party meeting downtown in some building. Sometimes Gaddar party meeting took place in the temple because we were all the same people. There was such a wonderful democratic approach to the whole thing that we are all brothers and sisters and we are going to be together in every bit of our effort.

9. Have your Sikh background ever inspired you in anyway like fighting the injustices and different things in your life?

Answer: Everybody's earliest training inspires them for what they do later in their life. My training was in the Sikh religion. I am not religious anymore of any kind of religion. I have to state that very emphatically because I don't think that one religion is better than another. I think that the important thing is that religions set out to teach us to be better people than we start out to be. That's what good about it. But then when all this separation start in and when one religion starts thinking that they are better than the others and then it's not good, because then war happens and everything terrible happens. I grew up in Sikh religion. I had a wonderful training. My father read from the Guru Granth Sahib every night and we all said prayers everyday. And of course all the prayers were aimed at making us realize that we had to be good and we had to be honest, we must not steal, we must not cheat, and we must not lie. Without this kind of early training perhaps my family wouldn't have had the character that I think we do have that we have always put the good of all ahead of our selfish game.  10. If you have to do all over again in your life, what things will you do differently?

10. If you have to do all over again in your life, what things will you do differently?

Answer: If I had it to do all over in my life then I would study Punjabi, so I would be better at it. My father taught me Punjabi, I would run along next to him while he would be ploughing in California. We came back to California after leaving Astoria, Oregon in 1922 and started farming. He had a worker with my mother who would teach my sister, who was a year and half elder than me, to read and write Gurmukhi (Punjabi) and my father would teach me. He would be out in farm and I would run along next to the horse with him and saying my muhavrey (Punjabi phrases). So I had a really good chance to learn it. It has pleased me so much that I can even now speak Punjabi even though I don't speak if for months and sometimes years and yet when I start speaking Punjabi again with our Punjabi people it comes back to me and it pleases others that I haven't lost it that I have retained the culture that I have grew up in and I haven't found anything to push it aside.

11. What changes you would like to see in America. So any thought on that?

Answer: I do have many thoughts on that. I would like to see the change to a society that looks upon all human beings as equal. If we're born human than we should have the same right to our two square feet on earth as anybody else especially if we're workers. We don't have to worry about what would happen to the rich because they don't worry about us. They are just out for the profit and the working people at the bottom of, what you call financial scale. We have to be together and the rich are all joined. They belong to their clubs which rules the world together and working people should have one big union. Forget about the country. They take the jobs away from American workers by closing down the factory here and setting it up in some other country where they pay just a ridiculous amount, which nobody can live on. Then they come back here and sell those same products at a great profit. The people in that country, who are making those products that were taken away from United States workers, should get together and have international union just like the industrial workers of the world. We have to fight back in anyway we can because world should belong to those who work and who can produce something and not to those who just live off of it.

12. Is there any message you like to give to the community you came from or a community at large?

Answer: I don't see myself isolated in any one community because I lived all my life among the people who discriminated against me in the beginning but now there is no need to give any separate messages. I would like to perhaps talk to my Punjabi sisters and say that they should understand that their work when they are making roti and dal in the kitchen is even more important than the work that the man does going out and earning some money and bringing it home, because that is the basis of life: raising the children, cooking, cleaning, all of that is the most important thing that anybody can do and its women who do it and they shouldn't feel like second class citizens in their family as many are often made to do.

13. Well Mrs. Kartar Kaur Dhillon that was my honor and privilege to talk to you. Do you like to add something or any closing remarks?

Answer: If there is anything I would like to add is that I have gone way past the worrying about discrimination. I have met so many marvelous people with whom I have joined in on demonstrations for justice, on various subjects against wars, against cruelty to immigrants who have come since my family arrived and I have so much hope for a just society because I see the very young people, some of them who are still in High School, recognizing what are their some of the problems, causes of their suffering and the cause is being that its not a just society. Few people hold everything in their possession and the majorities do not have it and there are so many young people who are recognizing that and refusing to go along with all of this unfairness. So they are the ones who are the hope of the world.

Acknowledgements: Camera by Kanwaljit Singh Kahlon and transcribed by Hemjot Kaur.

Pictures from Echoes of Freedom

Copyrighted material, please don't duplicate or reproduce parts or whole interview without author's permission.