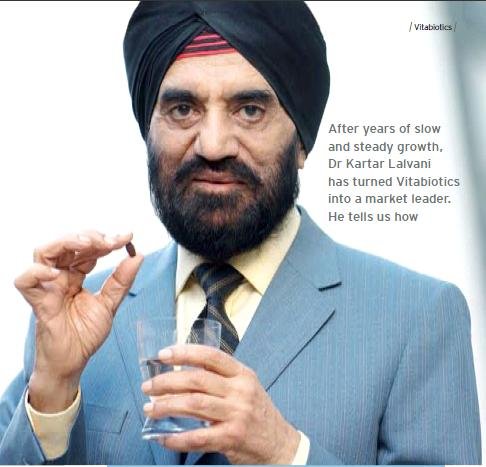

When Dr Kartar Lalvani founded Vitabiotics in London in 1971, it was the UK's only specialist vitamin supplement company. Today, the company produces a range of well-known brands, including Wellwoman and Omega-H3, which treat everything from mouth ulcers to menopause. The global Vitabiotics Group turns over about US$371m a year and is driven by Lalvani and his son, Tej. But it wasn't always plain sailing for the enthusiastic and modest Sikh businessman. Indeed, the company's roots were in adversity.

Lalvani was born in Karachi in 1931. His father was a successful pharmacist and the family lived comfortably. But in 1947, the partition of India forced them to flee to Bombay, where they had to start their lives over from nothing. Lalvani recalls it as a devastating period in his life. Aged just 16, he had to leave his secure, contented life and move to an unknown city more than 500 miles away.

In retrospect, he says that this period of turmoil was the making of him. "Without partition, perhaps my brothers and I would not have been so entrepreneurial," he says. "But because we witnessed my father losing everything, it made us determined that such a thing would not happen to us." This fear of failure is what drove him on in the early days and it still does, despite Vitabiotics' current success and his own personal wealth.

In the end, Lalvani followed in his father's footsteps and studied pharmaceutical science in London, Germany and India. But it took more than a good knowledge of the subject to succeed in the pharmaceutical sector. It was the way he applied himself to his studies, to research and then to setting up and growing the business that really made the difference.

Lalvani arrived in London in April 1956 at the end of one of the coldest winters on record. He threw himself into his studies and completed a postgraduate degree in pharmacy at King's College London. Then came a doctorate in medical chemistry at Bonn University in West Germany.

No pain, no gain

But it was a personal issue that led Lalvani into business. At that time, he suffered from mouth ulcers and had failed to find a treatment on the market that worked for him. They might alleviate the immediate pain, but they didn't cure the problem.

So, using a combination of vitamin C and powder taken from a diarrhea tablet, Lalvani managed to treat his condition successfully. The product, called Oralcer, would be the first in his new business's pipeline. By then, it was 1971 - and it was also where the hard work started. There were not many young Sikh entrepreneurs in London in the 1970s, and Lalvani found it difficult to get his ulcer treatment on the shelves of the larger high-street chemists, such as Boots. He then approached the UK's larger pharmaceutical companies, hoping to license his formula, but they too chose not to work with him.

There were not many young Sikh entrepreneurs in London in the 1970s, and Lalvani found it difficult to get his ulcer treatment on the shelves of the larger high-street chemists, such as Boots. He then approached the UK's larger pharmaceutical companies, hoping to license his formula, but they too chose not to work with him.

So convinced was he that his product worked that he set up his own company, Vitabiotics. Having spent all his savings on patenting the product, however, there wasn't enough money to launch it with much fanfare. So he began to visit individual pharmacies personally.

While this approach also proved fruitless - he only managed to sell £5 worth of Oralcer - Lalvani learned a valuable lesson about getting knocked back and having answers for any questions or concerns that were thrown at him.

Perhaps just as important as Lalvani's persistence and determination was the degree to which he was prepared to make sacrifices. He worked harder and offered a better level of service than anyone else - and learned to live on a meager budget. "I was always overworked," he says, "but happily overworked. I'd work 17 hours a day but be happy doing it." This was just as well as, in addition to trying to get Oralcer to market, Lalvani was working on his next product, a multivitamin called Omega H-3. He had also taken on his first employee and was taking his first steps into marketing and PR activity. It was with Omega H-3 that Lalvani got his first big break - but it didn't come through UK sales.

Lalvani's brothers, Gulu and Partap (see box, previous page), were also forging entrepreneurial careers. Partap was working in Nigeria, so Lalvani tried Omega H-3 there and it was a success. It was the impetus Vitabiotics needed.

But just when the time seemed right to expand, Lalvani hit a stumbling block common to all entrepreneurs: access to finance. Developing pharmaceutical products and setting up a new business isn't cheap, but the banks wouldn't lend to him. In fact, despite having had an account with the same bank since 1957, it wouldn't give him a loan. While this frustrated the rate at which Vitabiotics could grow, Lalvani says the experience forced him to focus, concentrate on value for money and approach expansion and investment with caution.

Today, Vitabiotics exports to more than 100 countries and has 20 UK brands, eight of which are number one in their markets. It employs 2,200 people and has factories and offices in six countries.

Lalvani may have struggled to find funding at first, but turnover is now about US$371m a year, with UK sales making up about 25% of that total.

These days, Lalvani works in partnership with his son Tej. The pair, along with Vitabiotics' Vice President and Marketing Director Robert Taylor, plan the future growth strategy of the company.

While Tej accepts that it is very much his father's company, both father and son see the relationship as positive and say they have no difficulties separating business and family life. And both hasten to add that it wasn't a case of Tej being given a senior position at Vitabiotics just because his father was the founder.

"I started out driving forklift trucks in a warehouse," says Tej. "But I wanted to do it that way - it is important to understand how all the different parts of the business operate and to see how important each part is.

Without borders

As Lalvani prefers to be based in the UK, it's down to Tej to lead the global business development of Vitabiotics and it's a busy period in the firm's history: It is building a new factory in Egypt, acquiring a manufacturing plant in Indonesia and looking to significantly expand its US presence.

It is building a new factory in Egypt, acquiring a manufacturing plant in Indonesia and looking to significantly expand its US presence.

"We look at the demographics of a country, the economic fundamentals, and generally start in a new territory by working with a distributor and going from there," says Tej. "If sales are strong, we then think about working with local partners or going into the country ourselves. For example, we are strong in Nigeria and India and we are looking to expand into Russia." But true to form, the team is cautious when it comes to doing deals and making investments in new markets. "It's been too easy to borrow money but then spend it in the wrong way," says Tej. "For us, it's about negotiating better deals, asking constantly for a better price and keeping on top of all costs at all times." But your business is only as good as your products, and they certainly seem to be working for Lalvani.

He may be 76, but he looks far younger and says he feels like he's 35. There's no denying the sparkle in his eyes and his palpable enthusiasm for his products. When he gives a demonstration of Vitabiotics' new anti-wrinkle cream, it's clear he is excited about the potential of this product, which has been 16 years in the making.

Indeed, Lalvani shows no signs of slowing down. He's just opened Indali Lounge, an Indian restaurant in London offering food based on the same approach he takes to his medicines - all natural, he says, and better for you than the usual ghee-based Indian cuisine. He's also just finished a book on India's colonial history.

While it has been a long, hard journey, Lalvani is fairly sanguine about what he had to go through to make his business a success. "I always had a vision, from a young age, that I would achieve something that helped other people," he says. "And I have."