I come from a lifetime in the pursuit of science, where I learned to weigh and value evidence and to separate the dross from the silver.

Even in science this is not always an easy matter;

much depends on the available literature that points to previous work done,

usually by other bench scientists in the area, and how dependable or

trustworthy it might be. And then much

hangs on the design of an experiment, the precision, accuracy and reliability

of the measurements, and finally the interpretation of the results.

Even in science this is not always an easy matter;

much depends on the available literature that points to previous work done,

usually by other bench scientists in the area, and how dependable or

trustworthy it might be. And then much

hangs on the design of an experiment, the precision, accuracy and reliability

of the measurements, and finally the interpretation of the results.

I still do a little science but now my energies increasingly go to reading and writing on or about Sikhi – a lifestyle that I find fascinating. In theory, any structure, culture or philosophic viewpoint that has existed awhile should be subjected to an evaluation much as a scientific hypothesis is, although it may not be replicable, as most scientific experiments are. (I also know that not all scientific hypotheses are open to testing by replication.)

The question here is the nature of the evidence.

Many human issues, admittedly of great significance — religions, nations, war and peace, for instance — are measured by the yardstick of history, which is often the only dependable criterion available. But how honest or reliable is it?

Since history is constructed of events that presumably had witnesses or can be substantiated by other mostly dependable, even if secondary, documentation, we like to think of what we fondly term “evidence based history.” That’s the best kind of history there is, if and when we have it. But is this the history that we always have? I would say more so in science, but not always; far, far less so in religions and cultures.

I had often thought about the vagaries of history but a news item that appeared just days ago breathed fresh life into the idea.

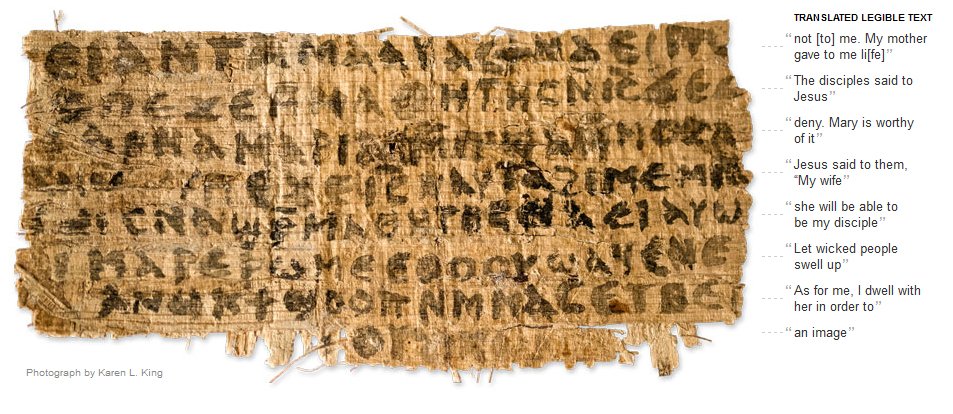

Professor Karen King, a historian at Harvard Divinity School, presented a fragment of a fourth century papyrus with some ancient Coptic writing. It seems to say, “Jesus said to them my wife….” And then a further clause refers to her as “…she will be able to…”

Does this mean that Jesus had a wife? Was he a married man? If so, would this not turn upside down the whole framework of Christian, particularly priestly, celibacy that is foundational to Christian belief and especially in the Roman Catholic Church?

Of course it would? But let’s not rush to judgment.

But is it the evidence-based history we are talking about? Wait a while yet to greet Mr. & Mrs. Jesus Christ.

What additional evidence exists and what does it suggest? Is there any evidence that may, even suggestively, corroborate or contradict this assertion that Jesus was a married man?

This new papyrus may date from around the fourth century AD; let’s say around the year 350 AD. The Gospels were written much earlier — by Mark around 70 AD, perhaps about 40 years after the crucifixion, the one by Mathew possibly another 20 years later. What do they say?

They write about Jesus, his mother Mary, his brothers James and Joseph, his sisters, even the followers Simon and Judas, but there is absolutely not a word of a wife. From the Gospels there are other similarly semi-convincing hints for both sides that Mary Magdalene either was or was not the wife of Jesus.

At least some years and heaven knows what circumstances elapsed between the crucifixion and the writers of these documents. Forget not that every writer may have a bias one way or the other. There are always open questions about the authenticity and provenance of a document. These are equally valid arguments and the truth, if and whenever it emerges, may turn out to be stranger than fact or fiction.

As an aside I mention that Sikhs universally accept the martyrdom of Guru Arjan as a fact. Yet, Bhai Gurdas, the noted Sikh savant, who worked closely with Guru Arjan, and was around at the time of the martyrdom, barely refers to it in his influential writings. Would this mean doubt about the martyrdom or its import in Sikh history? That would surely be nonsense.

Let me now take a leap in time to the 20th century and revisit some not so ancient history, and then we will jump again to a time in between the two, and then to the nature of history itself.

At the beginning of the last century did the fading Ottoman Empire create an Armenian Massacre? Not if you live in or visit Turkey; an affirmative statement might land you in jail. On the other hand, it is illegal if in France you deny that such a massacre occurred and the gendarmes might come after you.

Similarly for the Nazi-driven Holocaust and the number of Jews killed. It all depends on your source of authoritative history: products of Iranian scholarship and writers of that ilk, or scholars from the wider world.

Another poignant example: How many Sikhs were killed in the November 1984 carnage in Delhi, the capital of modern India? About 3,000 as the Indian government concedes, more than three times that number as some Sikh sources allege, or merely a negligibly small number, no more than a handful as some other loud voices in India proclaim, not without influential political support.

Do you think there is no history available for the three events? Do you think no documentation exists? Of course it does. Is all available history equally good? Should all evidence be disparaged, rubbished and dismissed. Not at all!

A notable historian, Harjinder Singh Dilgeer, asserts that the dramatic events of Vaisakhi 1699 may not have occurred in that year but a year or two earlier, in 1697 or 1698. I have personally heard a scholar who occupies a Chair of Sikh Studies aver that at Vaisakhi 1699, it might have been three and not five Sikhs who took amrit. I leave him unnamed because he did not publish it but stated it orally off the record.

Human records are rich with such events that are now difficult to document beyond doubt. Time takes its toll of history and also continues to uncover more history. The search for what is truth is never so simple, and never is it finished.

History does not come to historians in neat packages, clearly and closely argued, with the truth laid out on a platter. Historical layers reveal eternal truth, but never so easily. It emerges from records written by adversaries; competing accounts that point to contradictory sources and are sometimes self-serving or honestly forgetful; relics, letters, photographs, partial recollections, oral history and family accounts handed from one generation to the next — they all contribute to history.

And both time and memory continue to play tricks.

So, no written version of history is ever final. History remains an argument without end. It is a layered narrative that accumulates more layers as time marches on. We do not live in the past but the past surely lives in us. Every new generation interprets anew its traditions and historical narrative to make a coherent story.

History is not science.

History is tangled, contradictory and messy — but that is what we are. A continuing practice of centuries often creates and becomes its own evidence and writes its own reality that is no less valid and profound to the faithful.

Lest you think otherwise, mine is not a polemic against history, nor do I dismiss it. History makes us what we are. Be careful with it; treasure it and explore it honestly. Uncover the truth as you see it and be always open to unfamiliar evidence or a new analysis of it.

T.S. Eliot reminds us of the “cunning passages and contrived corridors of history that deceive us by vanities ….”

It

seems to me sometimes that if we don’t see how history takes life, if we do not

see its plasticity and its blind spots we then construct out of history a

prison for ourselves.

Related story: A Faded Piece of Papyrus Refers to Jesus' Wife