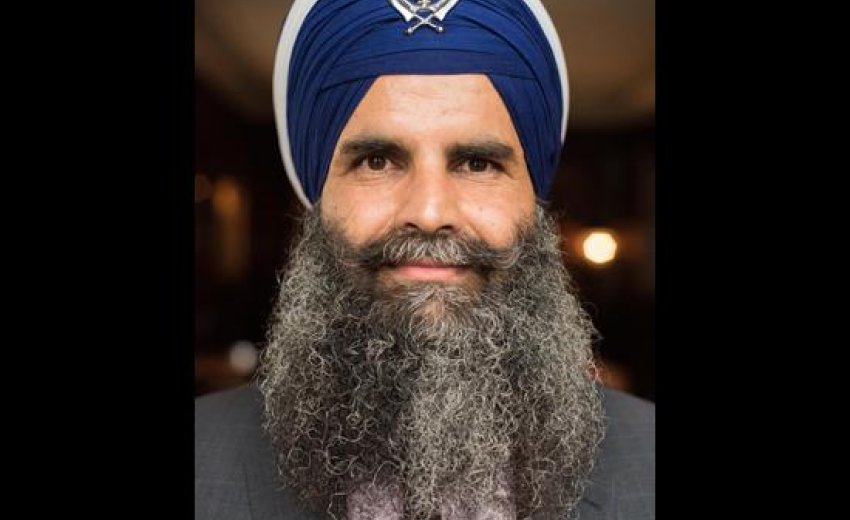

A moment of embarrassment in the Buffalo, N.Y., airport almost a decade ago put Gurinder Singh Khalsa on the path to political activism.

An entrepreneur and a real estate developer, Khalsa tried to board a flight home to Sacramento when he was stopped by a Transportation Security Agency agent. Remove his turban, he was told, or else he wouldn't be allowed to fly.

A devout member of the Sikh faith, Khalsa refused.

The long scarf wrapped tightly around his uncut hair, known as a dastaar, wasn’t just cultural paraphernalia from his youth in India. Always wearing it in public was an essential requirement of his faith.

“It felt very insulting, especially because it took place in front of so many other people,” Khalsa said. “I could have complied, but at that moment I decided I couldn’t.”

Khalsa, a U.S. citizen, did what many others do when they feel the government has failed them. He called a congressman.

That call led to organizing among Sikh-based organizations across the country, a lobbying effort in Congress, and a change in TSA headwear policy that now allows Sikhs to pass through airport security while wearing their turbans.

“I feel like I did a productive thing for my community, and for my country,” said Khalsa, who calls himself a proud American – and for the past eight years, a proud Hoosier.

Earlier this summer, Khalsa founded SikhsPAC, a political committee that aims to raise $5 million by the 2020 election.

As of early September, it had collected more than $375,000 and made donations to both the Democrat and the Republican candidates in races for governor, state schools superintendent and attorney general.

Its goal is to bring awareness to the estimated 10,000 Sikhs living in Indiana, many of whom are immigrants from India. They own 3,500 businesses here – many of which are gas stations, convenience stores and trucking companies.

Part of their awareness campaign is to teach others the significance of the turbans worn by Sikh men, and some women.

With 25 million adherents, the Sikh faith is the fifth-largest in the world, but Khalsa thinks it remains largely unknown. Ignorance fuels fear.

“People see it and they think ‘Osama bin Laden,” Khalsa said of the dastaar.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, images of the white-turbaned al-Qaida leader saturated the media.

“We became victims of violence,” he said. “People looked at the news and saw Osama in a head scarf, and they thought he was one of us.”

Since 9/11, the New York-based Sikh Coalition has reported 700 incidents of violence or harassment against members of the faith living in the United States.

Being visibly faithful is an integral part of Sikh life.

The religion, founded in 1469 in the Punjab region in India and Pakistan, teaches that people are essentially equal in God’s eyes.

Its founders, rebelling against India's strict caste system, exhorted followers to don the turban to symbolize that equality.

But it’s not just a political statement. It’s a declaration of humility before God, Khalsa said.

“To be asked to remove it is painful,” he said. “It’s a violation of our faith.”

Politically, Khalsa would like to see state education leaders encourage schools to add an explanation of the faith to a world cultures’ curriculum that already teaches students about Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, and Islam.

And he’d like the General Assembly to eventually pass a hate crimes bill -- legislation that's been rejected in the past.

Both ideas seem ambitious in the Statehouse, but Khalsa is an optimist. He is convinced Americans are willing to embrace diversity.

“In this country, if you ask for something, you can get it,” he said. “It’s what makes this country great.”