(This is the second article in a series, adapted from the script of The Story Of The Sikhs, a Sikh History podcast, written and narrated by Sarbpreet Singh. All ten episodes of Season One are now available. This story is from Episode 2 - The Wanderers

Read Part I here

A fabulous feast has been laid out. Mouth watering delicacies of every kind imaginable. Rich curries, mounds of fragrant rice colored with saffron and garnished with cashews, almonds and raisins. Trays heaped with succulent sweetmeats. It is a formal feast. A Brahma Bhoj. And it has been arranged by Malik Bhago, the richest man in the town of Sayyidpur. The large hall, festooned with streamers and decorated with flowers has been separated into four sections, the fourth one set apart from the other three by a great distance. In each section sit men in rows, banana leaves spread before them on which attendants heap endless mounds of food. The guests lick their fingers and smack their lips as they sample each new delicacy.

Amidst the feasting and revelry, sits Malik Bhago, resplendent in robes of silk with a regal turban on his head. His brow though, is furrowed and there is a frown on his face. He has organized this ritual feeding of the Brahmins, the priests, who sit at the top of the hierarchy of castes. It is an important occasion for it will rid him of the bad Karma that he has accrued in the past and might accrue in the future. It will grant all his ancestors absolution for their sins and will be their salvation. Befitting his status as a wealthy man, he has invited all the four castes to the feast and has spared no expense. A feast like this one, Sayyidpur has never seen before.

This should be a day of joy and triumph, but Malik Bhago's mind is not at peace. For, while the entire town has turned out to salute him and celebrate his power and wealth, there is one who has dared to defy him. Quietly but effectively. By simply not showing up!

Malik Bhago had decided to arrange a feast, the likes of which had never been seen in Sayyidpur before. A Brahm Bhoj required that only Brahmins be fed, but Malik Bhago had magnanimously decided to invite all the four castes and had sent his family priest, of course a Brahmin, to invite everyone.

The Brahmin had made his way to a humble hut on the outskirts of Sayyidpur, the home of a poor carpenter named Lalo. For he had heard that a holy man, a Faqir or ascetic named Nanak was living in Lalo's home. Nanak's presence in Lalo's home had set tongues wagging. For it was rumored that he was the son of a high caste Kshatriya. It was shocking and unseemly for him to be living in the hut of a carpenter, a low caste Shudra. The Brahmin haughtily informed Nanak of Malik Bhago's upcoming feast and bid him to attend, as all the four castes had been invited. Nanak refused, saying that as a Faqir he didn't belong to any of the castes. The Brahmin scolded Nanak, warning him that his strange ways had already given him an unsavory reputation and told him that he would incur Malik Bhago's wrath if he didn't attend. When Nanak refused, the Brahmin scurried to Malik Bhago and complained of his intransigence.

After the feast, the chagrined Malik Bhago sent the Brahmin back to fetch the impudent holy man but Nanak looked quizzically at him and refused to accompany him. What could Malik Bhago possibly want from me O Brahmin? The Brahmin hurried back to his master again in great indignation, complaining about the stubborn Nanak. He refuses your summons Lord. And such shameless behavior! The son of a Kshatriya consorting with a lowly Shudra!

Livid with anger, Malik Bhago sent his servants to drag the defiant Nanak to his presence. Upon hearing of Malik Bhago's anger, Nanak agreed to accompany them to his house and the little procession set out for the rich man's mansion with Lalo, fearful for Nanak's safety, following close behind.

How dare you turn down my invitation to the feast? Malik Bhago thundered, a hush settling in the room as he sat in his throne like chair, surrounded by his followers and household priests. Nanak, who stood humbly before him, replied that he was a Faqir and had no use for rich food or delicacies. His answer rather than placating Malik Bhago, only served to anger him even more. You call yourself a Faqir, refuse my food and dare to break bread with a lowly carpenter! Upon which Nanak softly asked, do you have any food to offer me now? Slightly mollified, Mallik Bhago sent the Brahmins to his kitchen to bring some food for Nanak. Nanak turned to Lalo, who stood close by, his hands clasped before him and his head bowed humbly and asked him to fetch some food as well.

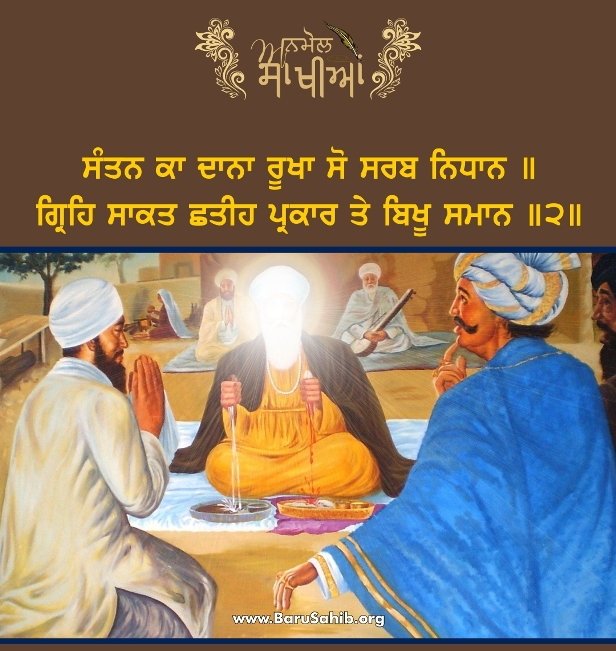

The Brahmins returned from the kitchen, bearing a hot and aromatic fried delicacy, known as a luchhi kachori. In a few moments, Lalo returned with a dry roti; coarse bread, made of kodri or millet, a humble staple of the poor. Nanak calmly looked at Malik Bhago as he grasped the fried delicacy in his left hand and the coarse millet bread in his right and squeezed. The assembly gasped in wonderment. Drops of blood dripped from Nanak's left hand. The rough millet bread, yielded drops of milk.

This is a story that every Sikh child hears growing up. For generations young Sikh children have heard many such stories about Nanak at their grandparents' knees. Some are wondrous tales of miracles that Nanak wrought, others are thinly disguised appropriations from Hindu mythology and some are based on historical fact documented and propagated through the generations. Nanak was above all else, a very rational and practical man, who spent his whole life debunking ritualism and pouring scorn on superstition. It is ironic that the legacy of a man who mercilessly exposed charlatans claiming miraculous spiritual powers, now swirls with fantastic tales!

Yet many of these stories are hugely important because in a simple, yet colorful manner they shed light on the ethos of the creed that Nanak was clearly building, brick by brick, throughout his life. Many of these stories come from collections of texts called Janam Sakhis, which can be loosely translated to 'Birth Chronicles'. Several of these texts have been preserved, some dating from the late 1500s and the others well into the 1800s. Many of them are contradictory and in some of them agendas, aligned with divisions that inevitably appeared as the faith progressed, are apparent. Many devout Sikhs treat the Janam Sakhi accounts with reverence and bristle at the suggestion that some of the stories might be apocryphal. Scholars of various stripes have published volumes of research arguing about their authenticity or lack thereof.

As a practising Sikh, particularly as a young man learning about his faith and then as a teacher of Sikh history, I have struggled with my approach to these stories. I have to come to accept them as parables, because without doubt many of them illuminate important truths and principles.

Nanak was a revolutionary. Even before he had his great epiphany, which gave him a sense of mission, he had pondered the human condition deeply. From his earliest years, he had been a keen observer of society and an uncompromising critic of practices that he saw as unfair. We have already delved into his brilliant assault on caste based discrimination.

It was a time of great social inequality where a feudal system added to the misery of the poor and the low caste. Historian D.N.Jha, in a paper titled Early Indian Feudal Formation, could have been describing the conditions of common peasants during the times of Nanak, suffering under the thumb of oppressive landlords like Malik Bhago:

In backward areas, where there was dearth of labour, peasants were required to perform free labour for the Landlord. In thickly populated areas, the practice of subinfeudation, implying the right to eject the cultivators, was well established which led not only to an oppressive collection of rent but also to reducing the permanent tenants to the position of tenants-at-will.

The parable of Bhai Lalo and Malik Bhago is a testament to one of the most important aspects of Nanak's world view. An unequivocal commitment to social justice! Nanak's tender heart chafed at the rampant exploitation that he saw around him. Fighting the insidiousness of economic oppression became a cornerstone of his new faith.

The rejection of Malik Bhago's rich food, dripping with the blood of the exploited and the embrace of Bhai Lalo's coarse bread, suffused in the milk of honest labor was a challenge to established social norms. And once again, Nanak was not content to merely draw attention to this injustice. He would go on to impart a way of life to his followers in which social justice was fundamental. And he would create institutions that would give his followers the guidance and the tools that they needed to live this new way of life.