INTRODUCTION

Diwan or Seth Todarmal is credited with paying an exorbitant amount of gold coins (mohran) to buy a piece of land to cremate the bodies of younger sons and mother of Guru Gobind Singh Ji. It is said that he was asked by Wazir Khan, the Mughal In-charge of Sirhind to cover the area which he wishes to purchase for cremation, with gold coins placed vertically covering the required for cremation. Thus, making it the costliest piece of land ever sold or purchased.

A few years ago, a hall in the historical Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib named after Diwan Todarmal was renamed Diwan Todarmal Jain. In this research paper, we will try to explore the identity of Todarmal through historical sources. Medieval history records several Todarmals and it seems it was a popular name at that time.

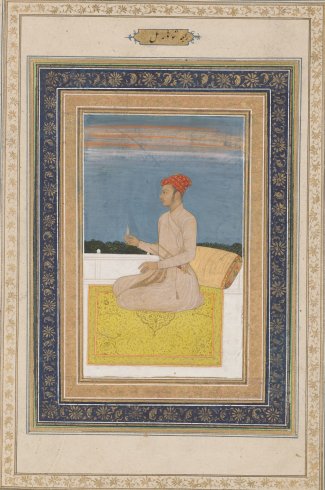

RAJA TODARMAL (D. 1589)

He is probably the most famous Todarmal of all and needs no introduction. He was the finance minister under Mughal ruler Akbar. The Sanskrit treatise Todarnanda commissioned by him states that he was a Khatri of the Tandon sub-caste.

Blochmann the translator of Ain-i-Akbari notes that the fame of Todarmal, as general and financier, has outlived the deeds of most of Akbar’s nobles. He along with Abul Fazl and Man Singh is the best known to the people of India at the present day.(1)

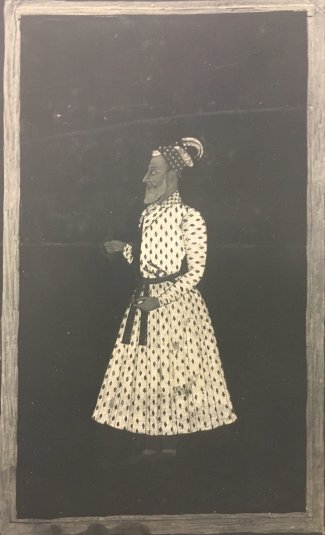

RAJA TODARMAL SHAHJAHANI (D.1666)

Todarmal was an official and initially, he was an associate of Afdal Khan, after his death, Todarmal around 1640 received the title of Rai, and was appointed Diwan (minister-in-charge of imperial finance), Amin (supervisor of the cultivation of arable land) and Faujdar (in charge of law & order) of the Sarkar of Sirhind. Next year he was given the additional charge as Faujdar of Lakhi Jungle. Pleased with the development of the territory in the following year, Todarmal was awarded a robe of honour, a horse, and an elephant by the Mughal Emperor. In c. 1643 his valuable services were recognised, and his rank was increased to 1000 foot with 1,000 horse, two-horse three-horse troopers. Three years later his rank was further increased by 500 foot with 200 horse, two-horse three-horse troopers. A year later (c.1647) he again received an increase of 300 horse, two-horse three-horse troopers. Gradually the charge for the management of the Sarkar Dipalpur (now in district Okara, West Punjab), and Parganas Jalandhar and Sultanpur was added to it. The annual revenue of these areas amounted to fifty lacs of rupees. He took proper measures for the collection of this amount and subsequently (c. 1648) he was exalted by promotion to the rank of 2,000 with 2,000 horses, and the grant of the title of Raja. During the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb, in 1660 he was for a time in charge of the Faujdari of Itawah (Etawah, Western Uttar Pradesh). After a very successful career, Raja Todarmal Shahjahani died in 1076 A.H. (1665-66 A.D.)(2)

The Dargah of Haji Baba Ratan in Bhatinda has a commemorative marble inscription that states that the tomb was whitewashed and repaired under the supervision of Jogi Das shiqqdar (revenue collector) under the ministership of Rai Todarmal in February 1643. This could be none other than (Raja) Todarmal Shahjahani.(3)

PANDIT TODARMAL JAIN (1719-66)

Pandit Todarmal was a scholar and leader of the Digambara Terapanthi sect of Jainism from Jaipur. He frequently lectured in the Diwan Badhichand Sah Temple at Jaipur. He wrote Hindi commentaries on important Digambara philosophy works and later independent works like Rahasyapurna Citthi (Spiritual Letter) in 1754 and Moksandrgaprakasaka. The latter is the most influential text of the Terapanthi tradition and is popular among Digambara Jains.

After his death, his younger son Gumaniram became the leader and in the 1770s he established a stricter set of ritual rules for his followers, and they came to be known as Guman Panth. They prefer to call themselves Suddh Terapanth Amnaya (The Pure Terapanth Tradition).(4) Terapanthis do not worship idols and consider such worship not to lead to salvation. They meditate upon and mentally worship those highly developed souls who have attained liberation.(5) In Guman Panth particular emphasis was laid on the purity of conduct of its followers.(6) The Arthasandrishttadhikara of Pandit Todarmal is a work of high merit in mathematics.(7)

Pandit Todarmal was born in 1719 and lived most of his life in Jaipur. The suffix Pandit is used to denoting his scholarship. He belonged to the Khandelwal community. Pandit Bakhtram Shah in Buddh Vilas (completed in 1770) states that Pandit Todarmal was arrested on false charges of uprooting the Shivpindi and was sentenced to death by the ruler of Jaipur. The sage was 47 years of age and was executed through trampling by an elephant. This corresponds to the year 1766 and the rule of Raja Madho Singh of Jaipur.(8)

TODARMAL (DAKHNI)

In 1698 Todarmal was made the sheristadar (chief officer) under Saadatullah Khan, Faujdar of Carnatic. In 1710 Saadatullah Khan was redesignated as Nawab and held this post till his death in 1732. (Lala) Todarmal acted as a representative of the Khan in diplomatic and revenue affairs.(9)

Todarmal visited Tirumala Temple (Tirupati district of Andhra Pradesh) and set up statues of himself, his wife, and his mother facing the main deity with folded hands.(10) One can infer that he did some real good to the temple during his lifetime.(11)

The said temple website states that the male statue is of Lala Khemarumu a Kshatriya who was known as Todaramallu. In the Tamil manuscripts, Todarmal has been referred to as Todarmallu. The website further adds that he courageously protected Tirumala from the invasions of Muslims and the British during the seventeenth century and ‘the Lord blessed this family and bestowed them with a place in his temple’.(12) The invasions and protection could not be verified as Saadatullah Khan is considered to be a peace-loving man(13) and the British were still a trading company only.

OTHER TODARMALS

Kailash Chand Jain (1963) in Jainism in Rajasthan states that in 1616, a Mantri (minister) by the name of Todarmal got constructed the door of Upasara (hall for prayers & meditation) in the state of Jaisalmer.(14)

None of the above is the Todarmal who made arrangements and perform the cremation of the younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh Ji and their grandmother in December 1704/05. Two eighteenth-century accounts refer to this Todarmal.

KATHA GURU JI KE SUTAN KI (C. 1760-65)

Katha Guru Ji Ke Sutan Ki is a mid-eighteenth-century poetic account of the martyrdom of the younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh Ji namely Sahibzada Zorawar Singh and Sahibzada Fateh Singh written by Bhai Dunna Singh Handuria. The poet identifies himself as Dunna Singh, Tarkhan (carpenter) Singh of Handur. The literal meaning of the title is the story of the sons of Guru Ji. Encyclopaedia of Sikhism informs that the manuscript was preserved at Sikh Reference Library, Amritsar under MS. No. 6045 until the Library perished in the army assault of June 1984. Luckily it was edited and published by Piara Singh Padam before, in 1967. The poem, based on internal evidence, was composed during 1760-65 and comprises of 122 chhands. The poet, Bhai Dunna Singh, had been with younger Sahibzades and their grandmother since they crossed the river Sarsa after the evacuation of Anandpur in December 1704/05. As per the poet, he accompanied them up to Saheri, where two Masands, Darbari and Dhuma, of the village of Saheri took custody of the family. As per the poem, a Sikh by the name of Todarmal conveyed the sad news of the execution of younger Sahibzades to their grandmother and later cremated all three of them after seeking permission from the authorities.(15)

GURU KIAN SAKHIAN (1790)

Guru Kian Saakhian, the literal meaning of the title is stories from the lives of the Gurus. It was written by Bhatt Swarup Singh Kaushish, of Bhadson, in Parganah Thanesar. The author records that the manuscript was completed at Bhadson in 1847BK (or 1790 CE). The original manuscript was written in Bhattachchhari, a script used by the Bhatts or family bards for recording genealogical details concerning their clients. It was later transliterated into the Gurmukhi script by Bhatt Chhajju Singh Kaushish in 1925 BK (or 1869 CE).

The author writes that while Guru Gobind Singh Ji was at Raikot hosted by Rai Kalha, Prohit Daya Singh came and told that the younger Sahibzades have attained martyrdom and this news was conveyed to him by Bhai Dunna Singh Tarkhan. Rai Kalha then sends his messenger Noore Mahi to Sirhind to get more details. When Noore Mahi came back, he informed Rai Kalha that he stayed in the house of Diwan Todarmal. The Sahibzades and their grandmother were put in the cold tower and tortured for four days and on the fifth day, they were martyred. After this sad event, Diwan Todar Mal Kapoor and his younger brother collected the three dead bodies and cremated them outside Sirhind town.(16)

MALWA DESH RATAN KI SAKHI POTHI (C.1823)

In 1876 Sirdar Attar Singh published an English translation of Malwa Desh Ratan Ki Sakhi Pothi written around 1823 under the title The Travels of Guru Tegh Bahadar & Guru Gobind Singh. The Sakhi 103 states that Rama Singh and Tiloka Singh, the sons of Sardar Phul came to meet Guru Gobind Singh Ji at Damdama Sahib. The Sangat commends them for cremating the Sahibzades. It is not clear if this refers to elder or younger Sahibzades as neither Chamkaur nor Sirhind has been mentioned.(17) Malwa Desh Ratan Ki Sakhi Pothi in Punjabi was published in 1950.(18)

Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha in Gur Shabad Ratanakar Mahan Kosh (Encyclopaedia of Sikh Literature) published in 1930 perhaps used this source and under Bhai Rama’s entry writes that Rama Singh and Tiloka Singh performed the cremation of younger Sahibzades. Under Todarmal, the author describes him as a resident of Sirhind and a Shahukar (money lender) who consoled Mata Gujri Ji after the martyrdom of Sahibzades. As per some historians, he (Todarmal) cremated Mata Ji and younger Sahibzades.(19)

In Tawarikh Guru Khalsa Padshahi Dasvi (1899), Giani Gian Singh refers to the above Sakhi but mentions that Ram Singh & Tilok(a) Singh went to Chamkaur and cremated the elder Sahibzades.

SURAJ PRAKASH GRANTH (1843)

Kavi Santokh Singh wrote the magnum opus in poetry known as Sri Gurpartap Suraj Granth and it was completed in 1843. Poet like Guru Kian Sakhian writes that Guru Gobind Singh Ji was at Raikot at Rai Kalha’s residence and despatches Noore Mahi to Sirhind to get more information. He returns and informs that Todarmal, a rich Sikh who intended to pay off the Mughals and secure the release of Sahibzades and their grandmother. However, on reaching the site he was made aware that Sahibzades had already been martyred. He then cremates the three dead bodies.(20)

Max Arthur Macauliffe (1909) almost follows the above accounts and writes that a rich Sikh called Todarmal cremated the bodies of the Guru Sahib’s mother and her grandchildren and buried their ashes.(21)

LATER ACCOUNTS - GUR PAD PREM PRAKASH (1881)

Sumer Singh wrote Sri Gur Pad Prem Prakash in 1881 in verse, and it was first published in 1939. The author refers to Todarmal Kapoor, a Sikh Khatri who performed the cremations of younger Sahibzades and their grandmother after paying a sum of money (Dhan) to the authorities.(22) It is not clear if the money was paid to the authorities so that they could release the dead bodies or if Todarmal was asked to pay for the land on which cremation could be performed. This seems to be the first source that states Todarmal had to pay money to the authorities.

Bhai Thakur Singh Giani (Vice Headmaster of Khalsa Branch School, Amritsar) wrote a small booklet titled Shaheed Bilas Arthath Sacchi Qurbani in 429 Nanakshahi (or 1898 CE) stated that Todarmal a rich Khatri Sikh who lived far way came and pleads before Wazir Khan to rescue the Sahibzades in exchange of his money and property. Wazir Khan declines and when Sahibzades are martyred, Sikhs (Todarmal is not mentioned) pay a large amount (of mohran) and are then allowed to cremate the young martyrs.(23)

GUR PUR PRAKASH (1919)

Sant Ren Prem Singh wrote Sri Gur Pur Prakash, a versified history in four parts of the Sikh Gurus. It was first published in 1919. The author claimed descent and that his main source was a rare manuscript dated 1709 by Bhai Binod Singh, a descendant of Guru Angad Dev Ji and contemporary of Banda Singh Bahadar. The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism which provides this information does not mention if any scholar has studied and verified the antiquity of this manuscript.

It states that Todarmal, a Sikh laid down the coins (mohran) on the ground for payment and sought permission (from authorities) to cremate younger Sahibzades and their grandmother.(24)

SIKH HISTORIOGRAPHY IN ENGLISH BEFORE 1970

It seems that modern historians (including Sikhs) of the 20th century while writing the history of the Guru period seem to have ignored Kavi Santokh Singh. John Malcolm (1812), JD Cunningham (1853), and Syad Muhammad Latif (1891) as early non-Sikh writers could be excused for not mentioning the cremation of younger Sahibzades.

Eminent historians who are silent of the cremation of the younger Sahibzades include History and philosophy of the Sikh religion by Khazan Singh (1914), A History of the Sikh People by Gopal Singh (1939), Evolution of the Khalsa Vol-II The Reformation by Indubhusan Banerjee (1947), Transformation of Sikhism by Gokul Chand Narang (1912, 1945, 1946), A Short History of the Sikhs Vol 1 (1469-1765) by Teja Singh & Ganda Singh (1950), A History of the Sikhs Vol 1 by Khushwant Singh (1963, 2004), Guru Gobind Singh A Biographical Study by J. S. Grewal (1967), History of the Sikh Gurus A Comprehensive Study by Surjit Singh Gandhi (1978) among others. There were very few exceptions and one of them was Life of Guru Gobind Singh by Kartar Singh (1951) which mentions Todarmal but the book is silent about the cremation of Sahibzades.(25)

Hari Ram Gupta in his famous work History of the Sikhs Vol 1, first published in 1978 writes that a local Banya Todarmal, a rich banker cremated the Sahibzades. The footnote refers to Kavi Sainpat’s GurSobha (1711) and Janamsakhi Guru Gobind Singh Ji written in Urdu in 1919 by Hakim Ram Kishan. The former may have been a printing error as GurSobha does not refer to the cremation of younger Sahibzades or Todarmal.(26) The History of the Sikh & Their Religion Vol 1 edited by Kirpal Singh & Kharak Singh and published by the SGPC also quotes Hakim Ram Kishan.(27)

SIRHIND THROUGH THE AGES

In 1972 Punjabi University, Patiala published the book titled Sirhind through the Ages edited by Fauja Singh. The book had articles by eminent historians on Sirhind in some detail.

Gurbux Singh mistakes Seth Todarmal with (Raja) Todarmal Shahjahani. The latter had died in 1666 hence he cannot be the same person and perform the cremation of younger Sahibzades in 1704/05. In the footnote, Gurbux Singh writes ‘the Sikhs cherish the memory of Todarmal as he purchased land from a Muslim Zamindar Chaudhuri Atta, by paying, in 1704, a fabulous amount of gold in order to get a place for the cremation for younger Sahibzades & their grandmother’.(28) Fauja Singh & M.S. Ahluwalia make the same error and state Seth Todarmal and Todarmal Shahjahani as the same person. The historians took a slightly cautious approach and write ‘the name of Raja Todar Mal is greatly revered by the Sikhs. It is said that he purchased a piece of land from a local Chaudhuri at a very heavy price and made arrangements for the cremation of the Tenth Sikh Master’s mother and his younger sons, Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh. If this is true, he must have enjoyed a very long span of life.’(29)

Kirpal Singh (& Fauja Singh) make the same oversight and states Todarmal, a Mughal official is the person who cremated the younger Sahibzades. Further, they add that Todarmal had to pay a large sum to Chaudhuri Atta to get a piece of land for the cremation of younger Sahibzades and their grandmother.(30)

This was perhaps the first time in textual sources (as far as the writer of this article could find) Chaudhuri Atta was named as the person who sold the land for the cremation. None of these historians provide a reference for it but correctly refer to Wazir Khan as the Faujdar, Amin and Diwan for the Sarkar of Sirhind, unlike the popular tradition which states Wazir Khan was the Subedar or Governor. Sirhind was not a Suba or province during this period.

CONCLUSION

Guru Kian Sakhian refers to Dunna Singh Tarkhan who must be the author of Katha Guru Ji Ke Sutan Ki. Both sources mention Sahibzades and their grandmother staying at the house of Karim Bakhsh Macchi and then at Saheri, they went along with two Masands although their names are not stated in Guru Kian Sakhian.

Katha Guruji Ke Sutan Ki and Kavi Santokh Singh refers to Todarmal as a Sikh. Latter states he is a rich Sikh. All sources state or suggest Todarmal was a Sikh (not a Khalsa). This should once and for all resolve the ongoing debate if he was a Jain.

Guru Kian Sakhian addresses Todarmal as Diwan Todarmal Kapoor. It is safe to assume he was an influential person who moved within official circles as he felt brave enough to ask and was granted permission to cremate ‘rebels of the state’ as Sahibzades were dubbed in the court of Wazir Khan. Bhatts are experts in keeping genealogy details hence when Swarup Singh Kaushish states Todarmal as Kapoor (a Khatri) it must be taken seriously.

Intriguingly, Guru Kian Sakhian refers to Todarmal as Diwan. Sirhind through the Ages correctly states that Wazir Khan was the Faujdar, Amin & Diwan of the Sarkar of Sirhind. Hence Todarmal could not be Diwan in the court of Wazir Khan. It will be an assumption to suggest that he may be the grandson or descendant of Todarmal Shahjahani and that he was named and out of respect the locals use the suffix Diwan after his illustrious grandfather or ancestor.

He was referred to as a Shahukar (money lender) only in twentieth-century sources. Speculation regarding such an important personality in Sikh history should be avoided. It is fine to admit that we have limited information on Todarmal. By adding myths to any historical figure, we do a huge disservice to them and the wider community as eventually questions may be raised regarding the authenticity of their existence.

~~~

REFERENCE

1. D.C. Phillott (1977) The Ain I Akbari by Abul Fazl Allami translated by H. Blochmann Vol 1. 3rd ed. New Delhi: Oriental Books p376-79

2. Baini Prashad (1952) The Maathir ul Umara by Shah Nawaz Khan. Translated by H. Beveridge. Vol 2. Calcutta: Asiatic Society. P957-58

3. Subhash Parihar (2002) The Dargah of Baba Haji Ratan at Bhatinda. Islamic Studies. Vol. 40. No.1 p113

4. Kristi Wiley (2004) The A and Z of Jainism. New Delhi: Vision Books. p220-21

5. Kailash Chand Jain (1963) Jainism in Rajasthan. Sholapur: Gulabchand Hirachand p92

6. Ibid. p93

7. Ibid. p175

8. Hukamchand Bharill (1973) Pandit Todarmal Vyakitva aur Krititva (Hindi). Jaipur: Samarak Trust p53-56. (This is the PhD Thesis of Dr Bharill submitted to Indore University)

9. Muzaffar Alam & Sanjay Subrahmanyam (2012) Writing the Mughal World Studies on Culture & Politics. New York: Columbia University Press. p369, 372

10. N. Ramesan (1999) The Tirumala Temple. 2nd ed. Tirupathi: Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams p41

11. T.K.T Viraraghavacharya (2003) History of Tirupati Vol II. 2nd ed. Tirupathi: Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams p625-26

12. Accessed on 18th February 2023 https://www.tirumala.org/TTDTempleHistory.aspx

13. T.K.T Viraraghavacharya (2003) op. cit.

14. Kailash Chand Jain op. cit. p40

15. Chetan Singh (2018) Sahibzadiyan de Shaheedi Parsang (Punjabi). Walsall: European Panjabi Sath p43-44

16. Piara Singh Padam (1986) Guru Kian Sakhian kirt Bhai Swarup Singh Kaushish (in Punjabi). Amritsar: Singh Brother p163-64

17. Sirdar Attar Singh (1876) The Travels of Guru Tegh Bahadar & Guru Gobind Singh. Lahore: Indian Public Opinion Press p113-114

18. Malwa Desh Ratan Ki Sakhi Pothi (in Punjabi) Khalsa Samachar, Amritsar (1950) p 111-112 (Available on Panjab Digital Library website)

19. Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha (1990) Gur Shabad Ratanakar Mahan Kosh (Punjabi). Bhasha Vibhag, Patiala. 5th ed. p552

20. Ajit Singh Aulakh (2007) Sri Gurpartap Suraj Granth Sateek Vol 11 Part 3 (Punjabi). Amritsar: Chattar Singh Jiwan Singh p318-321

21. Max Arthur Macauliffe (1909) The Sikh Religion Its Gurus, Sacred Writings & Authors Vol V. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p198-99

22. Achhar Singh Kahlon (2000) Sri Gur Pad Prem Prakash Krit Baba Sumer Singh (Punjabi). Patiala: Punjabi University. p388

23. Bhai Thakur Singh Giani (1898) Shaheed Bilas Arthath Sacchi Qurbani (Punjabi). Amritsar: Wazir Hind Press. p66-72

24. Sant Ren Prem Singh (1965) Sri Gur Pur Prakash (Punjabi). 4th ed. Amritsar: Giani Press. p1889-90

25. Kartar Singh (1951) Life of Guru Gobind Singh. 2nd ed. Ludhiana: Lahore Book Shop p189-90 (In 3rd ed. of 1968, Todarmal buys the requisite piece of land by paying gold mohars which completely cover it up the land and he cremates the Sahibzades p. 190)

26. Hari Ram Gupta (1984) History of the Sikhs Vol. I The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. 2nd ed. Delhi: Manohar p209 (reprint 2008)

27. Kirpal Singh & Kharak Singh (2004) The History of the Sikh & Their Religion Vol. 1.3rd ed. Amritsar: SGPC p306

28. Fauja Singh (1972) Sirhind through the Ages. Patiala: Punjabi University p41 (available of Panjab Digital Library website)

29. Ibid. p79-80

30. Ibid. p142

This research was originally published in the April-June 2023 issue of 'Abstracts of Sikh Studies Journal'